For the first time this year, Godot participates in the Google Summer of Code (GSoC). We have five students working on some great projects to add new features to the engine, either via C++ modules, GDNative plugins or external plugins. See our previous announcement for a quick presentation of each topic.

I’ve asked all students to write a short progress report about their projects, which are all in the last stages of development for the GSoC internship. We’ll have another progress report next month once their work has been finalized and integrated in the engine. Here are short links to the reports on the five projects:

Godot Blender exporter – Jiacheng Lu

- Project: Blender addon to export Blender scenes to Godot’s native scene format

- Student: Jiacheng Lu

- Mentors: Geoffrey Irons and Juan Linietsky

- Repository: https://github.com/godotengine/godot-blender-exporter

The “Godot Blender exporter” is an addon for Blender that exports Blender scenes directly to Godot’s native scene format (.escn, which is the same text format as .tscn but will be converted to the binary .scn format on load for performance), without using an intermediate asset exchange format. This is meant to become the main workflow for working with Godot and Blender together.

After implementing all the features that are already supported by the intermediate formats like Collada and glTF, this project will focus on adding support for Blender Cycle and EEVEE (2.8+) materials, so that you can convert them to Godot SpatialMaterial easily with the addon.

How it’s like to work with Godot

Best programming experience I ever had. It is a combination of being free and being offered with great help.

I have the freedom to arrange my time and set my own plan, it feels like no pressure at all. And I am free to choose how to finish my work, while the community encourages me to be as creative as I can.

Meanwhile, I enjoyed great help from the community. I am mentored by sdfgeoff and reduz. sdfgeoff is so responsible, he carefully reviews all my commits down to every line of code. reduz is always quick to respond on IRC, although he is busy developing new features for Godot (during that time, he finished the new Animation editor, the new AnimationTree and visual shader editor. Amazing!!). And there are other people voluntarily testing new features, helping me with documentation and so on. Thank you all!

Current stage of exporter

After about three months’ development by sdfgeoff and me, I am confident that the current Godot Blender exporter almost has support for the same functionalities as Godot’s popular “Better” Collada exporter. It now supports meshes, armatures, lights, cameras, shape keys, animations (including object transforms, pose bones and property changes in shape keys, lights and cameras), and an automatic material search.

Besides, users have reported that exporting shape keys in the Godot Blender exporter is a little more efficient than the Collada exporter. Also, I believe it will also be more efficient for exporting animations thanks to using a different implementation to the Collada exporter’s.

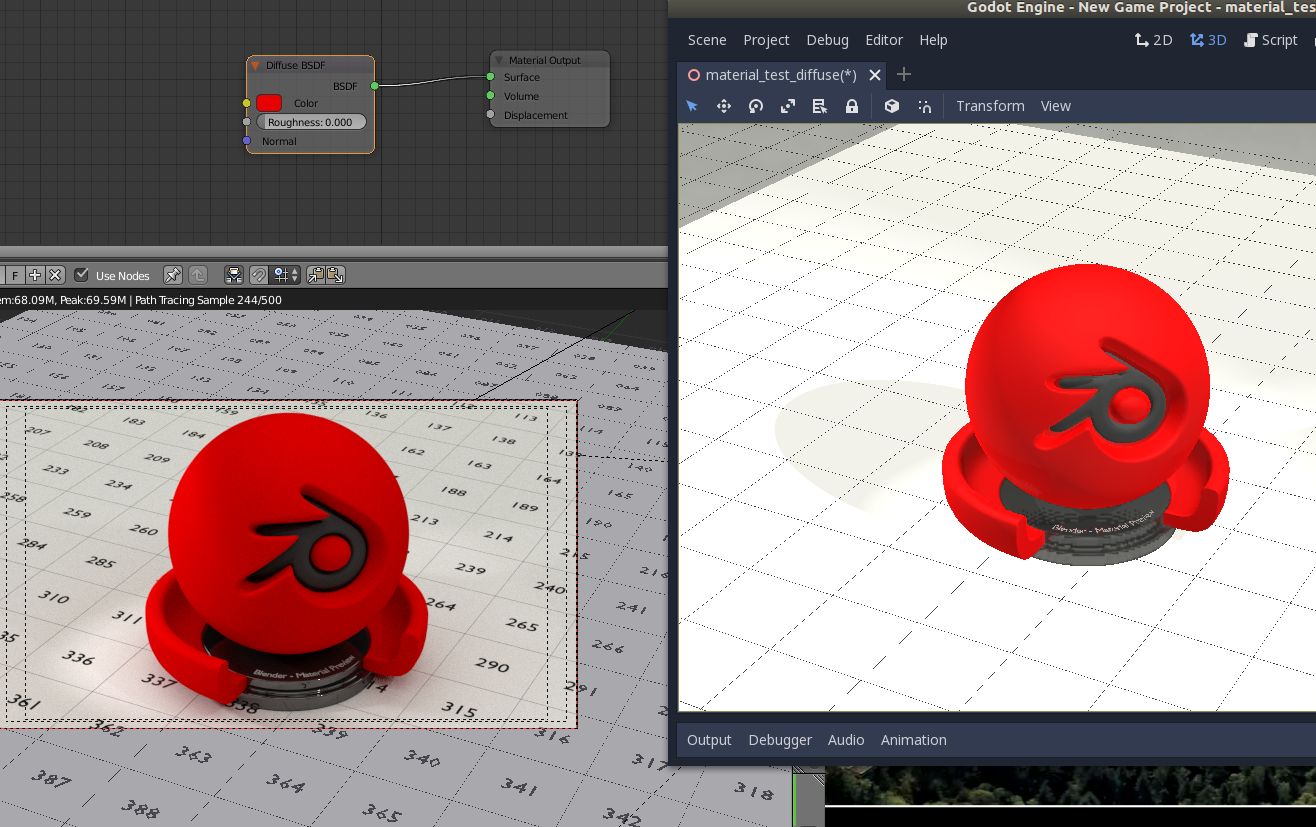

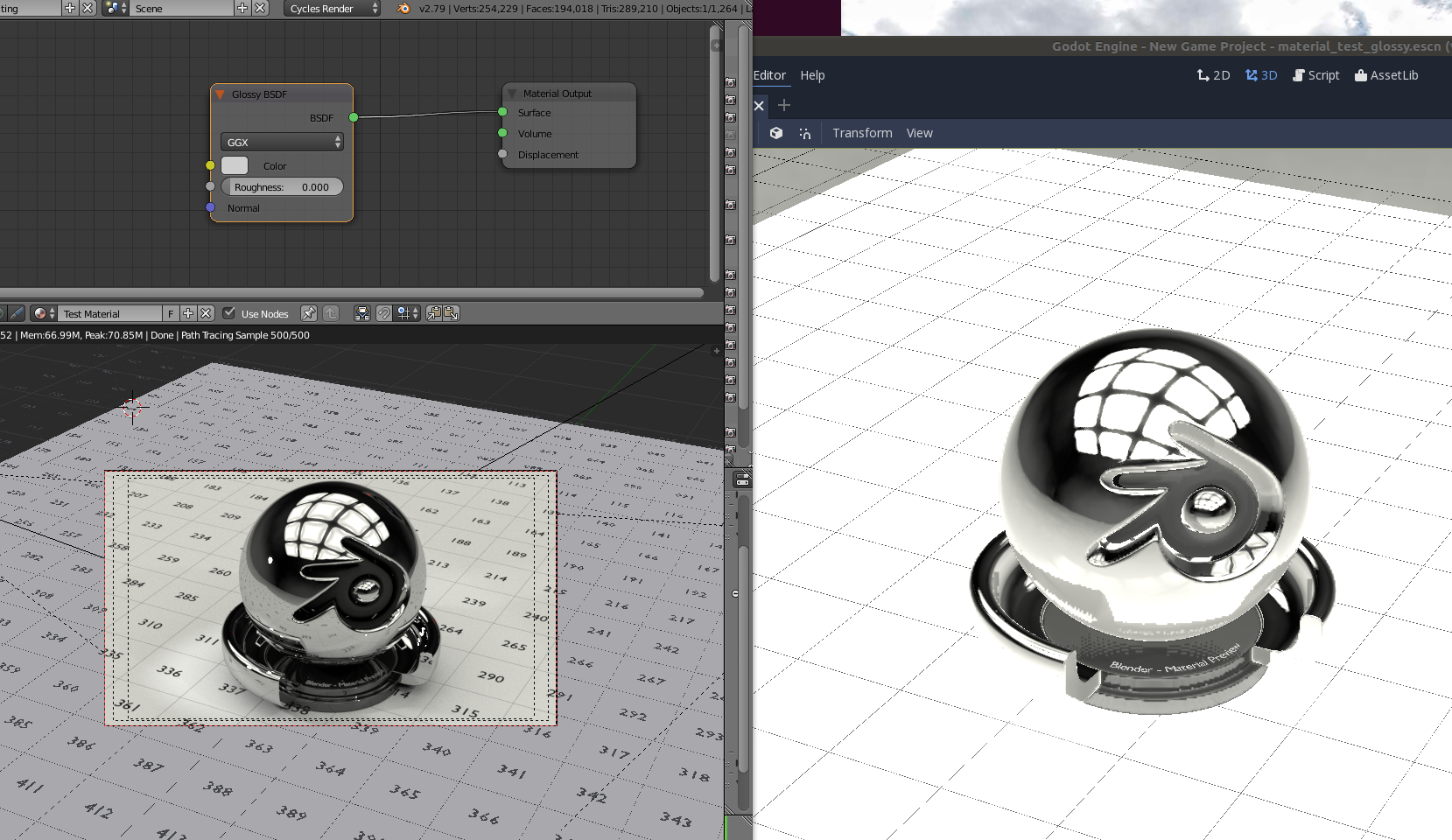

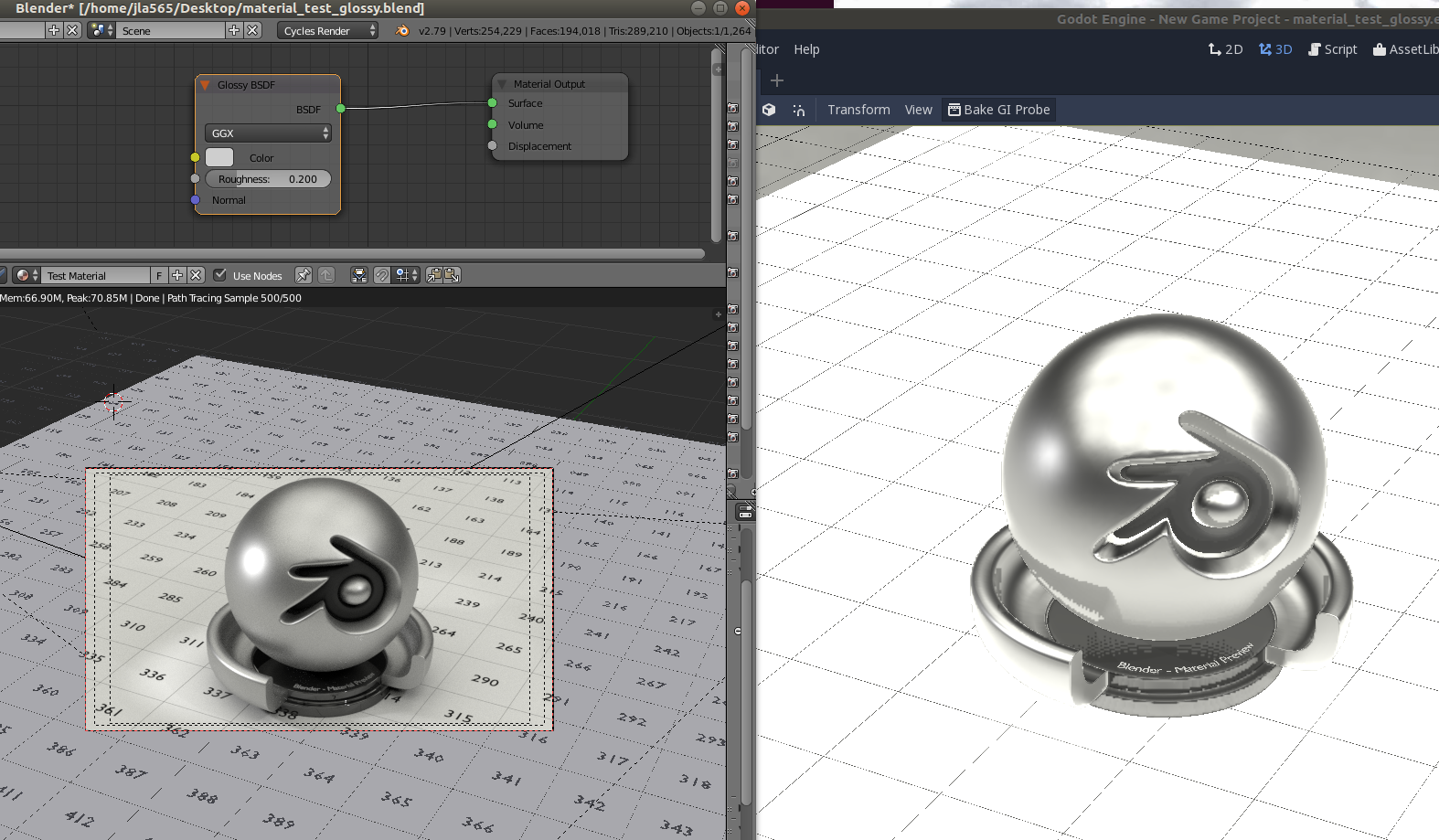

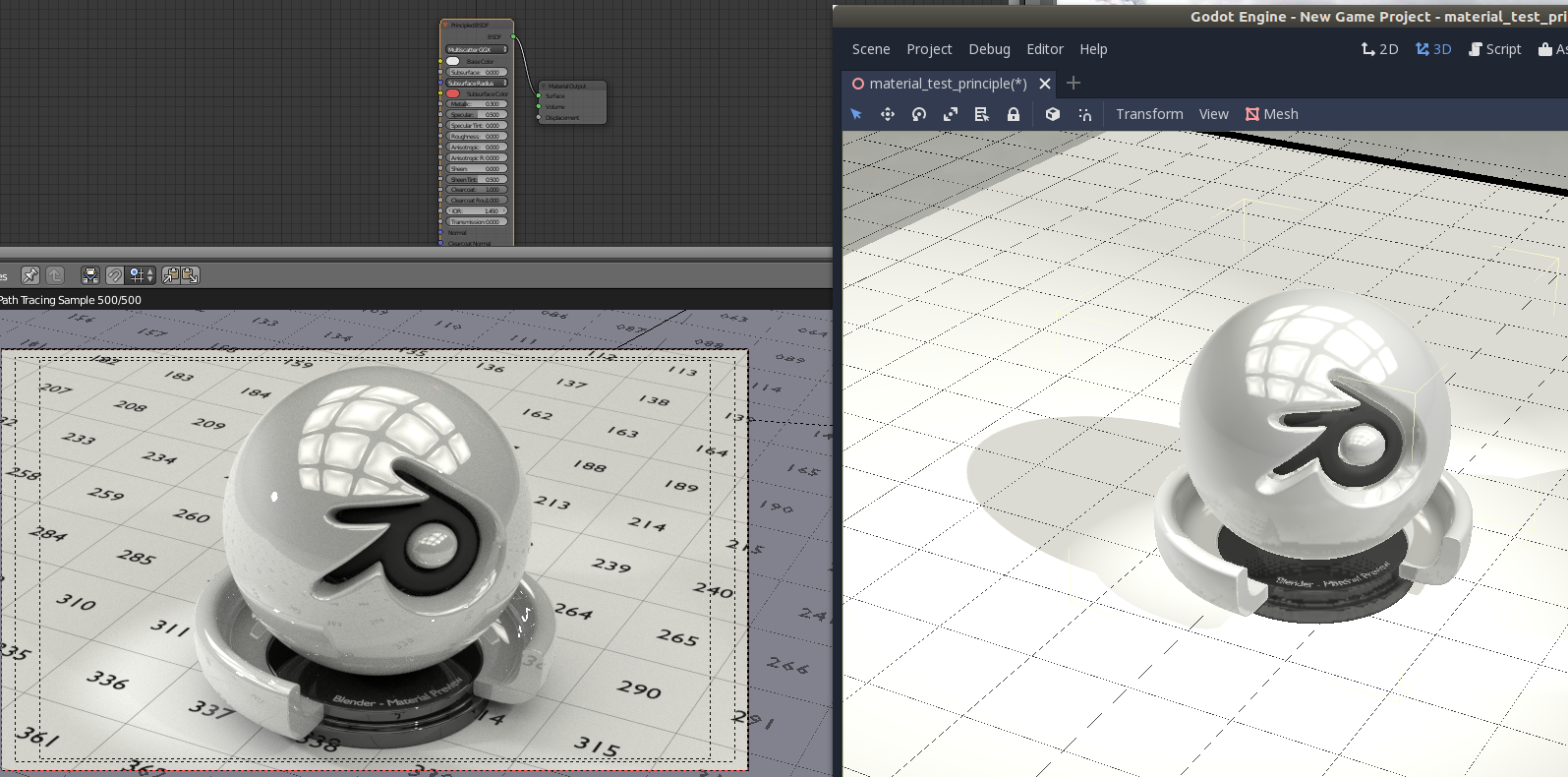

The main focus of this GSoC project which is supporting Cycle materials is about to come. Textures, normal maps and some of the BSDF shaders are already well supported.

Here are some examples of recent progress made on exporting Cycle materials:

Future steps

First, I will keep improving material exporting, for example the transparency and refraction properties are not well converted right now. Then I will spend one or two day to support the material of Blender 2.8’s EEVEE render engine. The addon API changed a little bit in Blender 2.8, so some work will be needed to update the plugin.

In parallel, I will keep the exporter updated along with Godot. There have been lots of new things (Godot improves so fast!) happening in the master branch recently, I will try to make use of them, for example the new animation editor and bezier interpolation.

Using the addon

You can already use and test the addon with Godot 3.0+. Download the repository and follow the installation instructions in the README.md to install the addon in Blender.

Extensive instructions on how to use the exporter’s many features are available in Godot’s documentation.

Keep in mind that this is a work in progress, so please report any issue you’re facing on the addon’s GitHub repository.

MIDI and SoundFont support – Daniel Matarov

Hello everyone! My name is Daniel and I am currently working on implementing MIDI support for Godot Engine, as part of the Google Summer of Code program.

My mentors are George Marques (vnen), Gilles Roudiere (Groud) and Marcelo Fernandez (marcelof). It has been a pleasure to work with them on this project and they have been very helpful and patient with me, as I am quite new to programming but nevertheless have managed to get everything to work so far, and I am quite happy with that!

The project aims to implement an existing MIDI library’s functionalities in Godot. Initially we were going to use FluidSynth, however we later discovered that it can’t work with the engine, so we decided to use a very simple and easy to implement library called TinySoundFont. It uses SoundFont files which are basically sample libraries, which the user can create themselves with external software like Polyphone and also MIDI files which can be played back. MIDI files contain sequences of MIDI notes, however the user can also choose to play single notes.

So far I have managed to implement most of TSF’s functions and also create resource importers for MIDI and Sound Font files. The way I chose to go about this project was to create a MidiStream class which inherits AudioStream and add the TSF functions to it. Using MIDI in Godot happens with using GDScript functions and also with the latest additions you can drag and drop or simply load SoundFont and MIDI files in AudioStreamPlayer’s inspector.

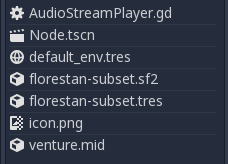

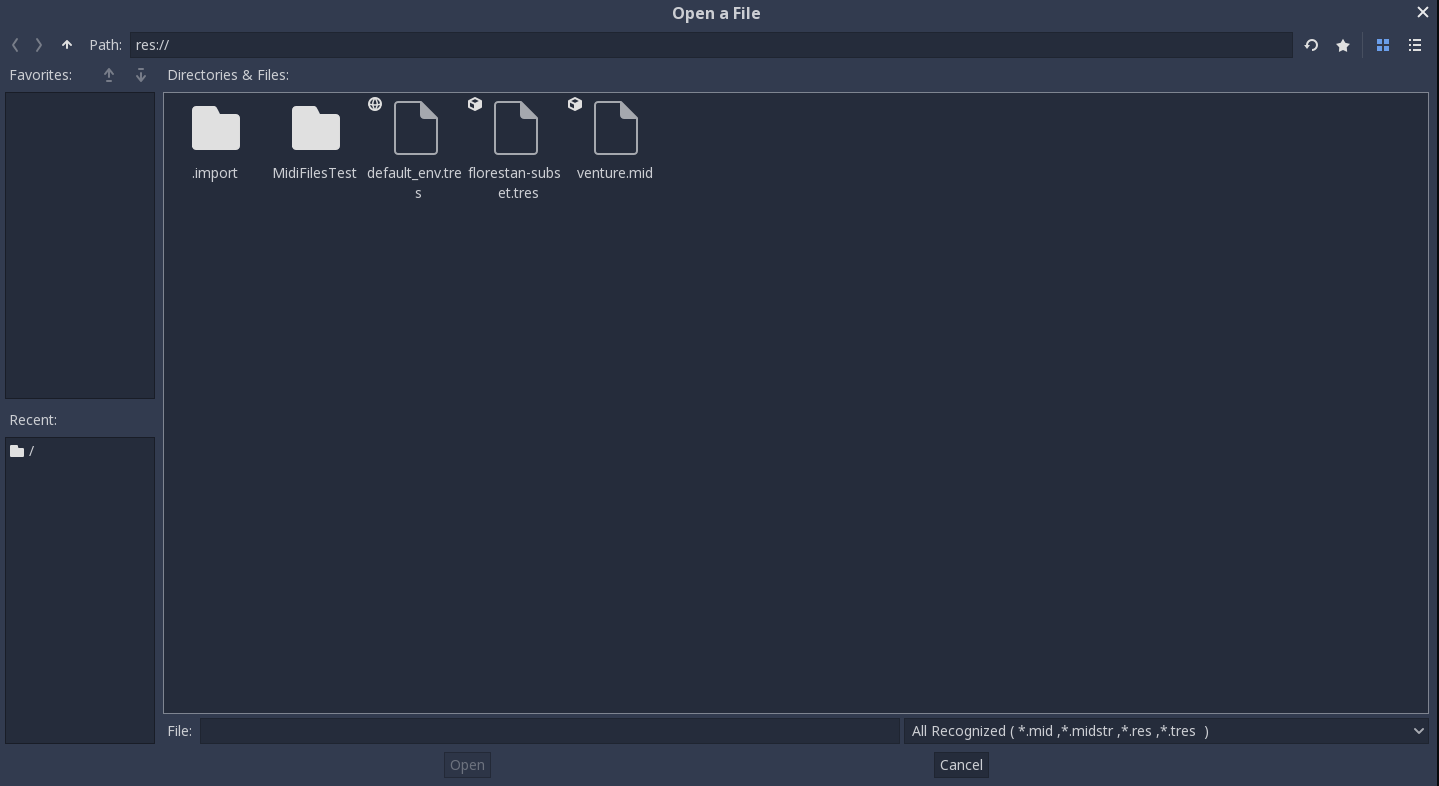

Here you can see SoundFont and MIDI files in the resource panel of Godot’s editor. For this example I have a soundfont and a midi file. There is also a .tres file for the Sound Font. The reason for this is that the files need to be reimported to be able to get playback from a midi file.

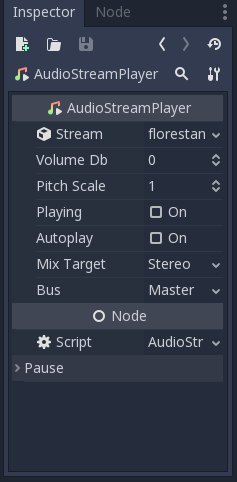

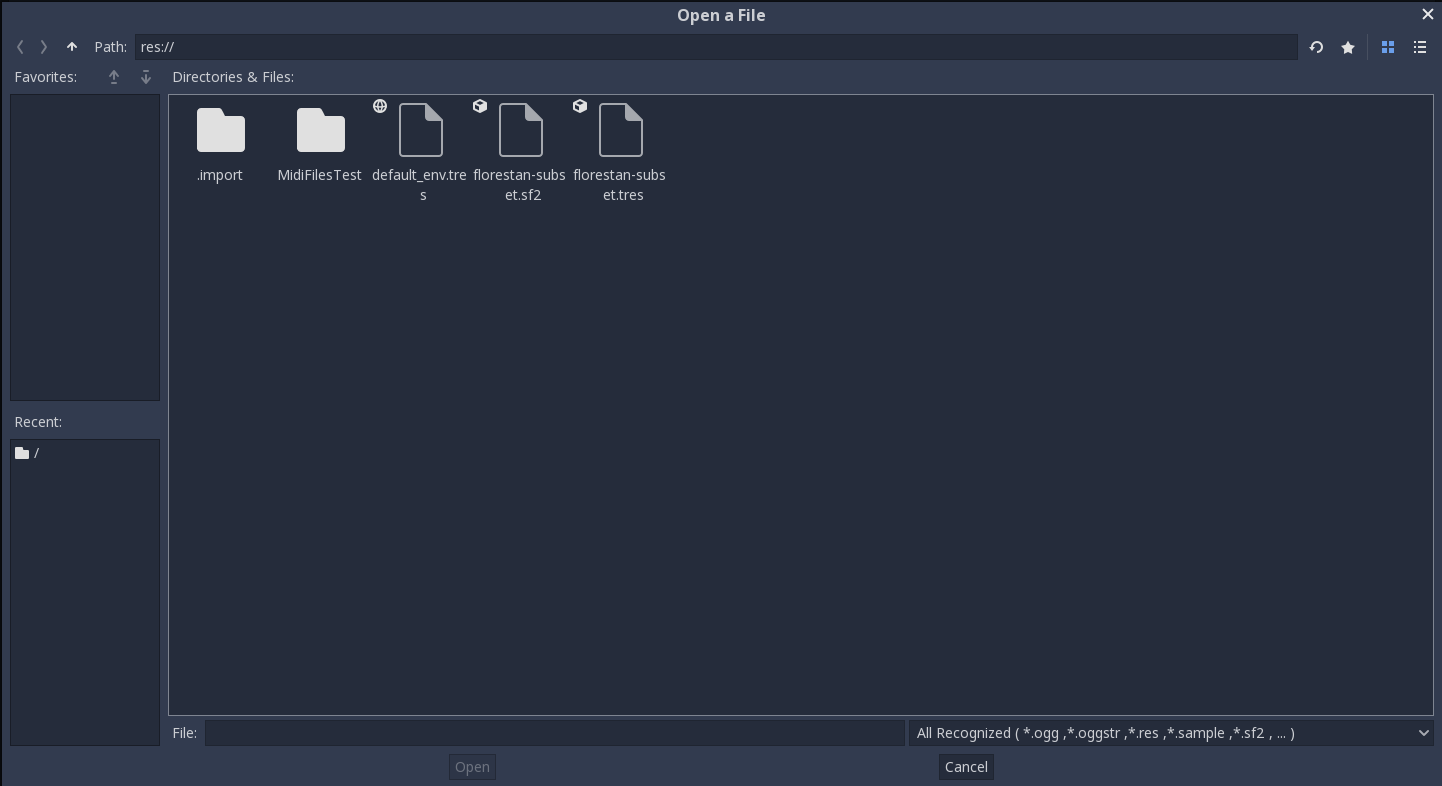

AudioStreamPlayer’s inspector with a sound font loaded onto the Stream property. You can either drag and drop the Soundfonts from the resource panel or load them by clicking on the arrow on the property and selecting load. You will get this screen where you can load the SoundFont.

To get sound you need to add a script to your AudioStreamPlayer node and use the note_on (note, velocity) function. There is no documentation for all the functions yet but that will be added in the future.

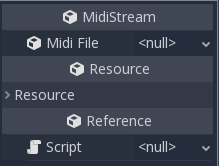

Loading the MIDI files happens in a similar fashion to SoundFonts. The way I handled importing them was by creating a separate resource for midi files and added a property to MidiStream which loads them. Here is what that looks like in the editor:

As of now I am doing a clean up of the code and adding comments to what I’ve done so far. As mentioned previously I will also make documentation for the feature and possibly add some other functionalities that I’ll need to discuss with my mentors.

Here is a link to my branch and the code I’ve written so far: https://github.com/DanielMatarov/godot/tree/MidiStream.h/modules/TSF

GDNative video decoders – Anish Bhobe

- Project: GDNative plugins for video decoding

- Student: Anish Bhobe

- Mentors: HP van Braam and karroffel

- Repository: https://github.com/KidRigger/godot-videodecoder and https://github.com/KidRigger/godot/commits/gsoc-pr

What’s the project?

The project is to make an interface that can be exposed to GDNative so that anyone can easily add video decoders to Godot by means of GDNative libraries. (Lets call them plugins, shall we?) Along with this, the plans are to release a small set of plugins that can take care of as many popular codecs as possible.

We are using FFmpeg for the codecs in the plugins.

This project is a part of Google Summer of Code program which makes it a learning opportunity for me (Anish Bhobe) under my mentors HP van Braam and karroffel.

Scope of the project

Initial plan was to have a system that automatically recognizes the format and selects appropriate codec/plugin. Then decoding shall happen such that all the user shall see is a new option in stream. The change here is that with the new interface, the selection is taken care of automatically without us having to write a new system. Other than that all the initial plans stay current, such as having a full interface for all video needs, and having plugins that can support a rather large array of codecs. (Thanks FFmpeg!)

So what’s done?

So far, video and audio playback (in sync) with good performance (at 480p) beyond which I haven’t tested the plugin. Audio was a tiny bit hard.

You can see the current state in this video:

Left to implement:

- Ability to load multiple plugins.

- Finishing interface, removing redundant functions, and adding a few not-so-obvious but required ones.

- Documentation.

- Fixing Memory Leaks (precautionary).

- Performance edits (depends on performance at higher resolution).

Future

- Running plugins on a different thread.

- Tutorials for using and making plugins, and a few for FFmpeg.

WebRTC support for multiplayer games – Brandon Makin

- Project: Support for WebRTC data channels both natively and in HTML5

- Student: Brandon Makin

- Mentors: Fabio Alessandrelli and Max Hilbrunner

- Repository: https://github.com/BrandonMakin/godot/tree/webrtc_static_final and https://github.com/BrandonMakin/Godot-Webrtc-test-project

WebRTC is an open standard for real time, peer-to-peer communication in the web browser. We will soon have a GDNative plugin allowing game developers to easily use WebRTC in Godot via Godot’s high level networking. The benefit of WebRTC is twofold:

Networked multiplayer on the Web

Networked multiplayer in web browser games has historically been difficult. Most HTML5 projects use WebSockets to send lightweight packets from the browser over TCP. UDP is generally preferred for games because UDP is unordered - lost packets do not block newer packets from being sent. However for security reasons, UDP cannot be sent directly from or to the browser. WebRTC is the only way to send UDP in the browser, so it’s the best way to make real-time web games with minimal latency. Many web games abstain from using WebRTC because of a perceived complexity of the peer signaling process (more on that later).

Peer-to-peer networking

WebRTC is peer-to-peer, meaning that data is transferred directly between two clients without having to go to a dedicated server. Normally, talking directly between two personal computers is made difficult by personal network’s firewalls and by a process called network address traversal. Devices are assigned a private IP address by their router, which has its own public facing IP address. WebRTC lets users make a tunnel through their firewalls, and it has a signaling process that allows two clients to tell each other their networking landscape.

WebRTC in Godot

WebRTC will run on both native exports and HTML5 exports and will allow communication between native and HTML5. It will be implemented as a lightweight module built in with the engine, but without any of the third party code needed to run natively. Because the third party code is large, it will be available as a GDNative extension in the asset library. Without the extension, WebRTC can only be used in HTML5 exports.

How it will work

Eventually, the docs will contain a complete tutorial for using WebRTC in Godot.

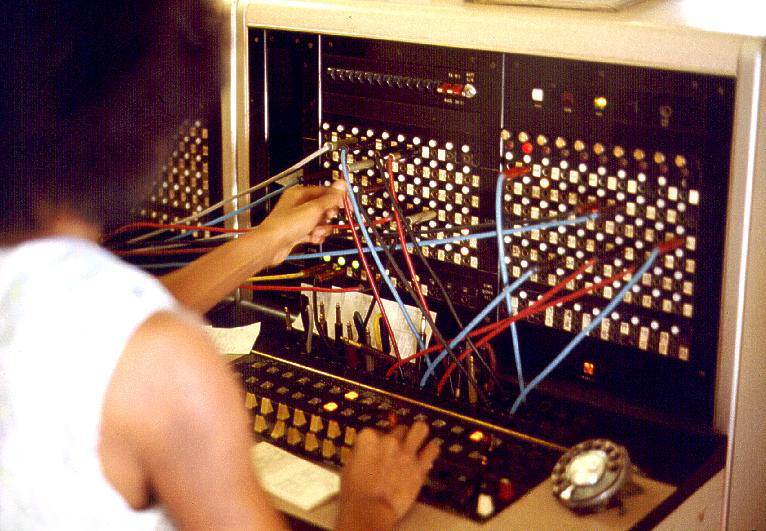

Even though WebRTC is peer-to-peer, it’s not truly serverless. Before two clients, or peers, can talk directly, they must use a signalling server to set up a connection. The signalling server doesn’t communicate any game data. It only signals the presence of two or more peers. Think of the signaling server like a telephone switchboard operator, connecting up two phone lines together. One peer calls, and the operator can connect it to another available peer so the peers can then communicate directly.

Telephone switchboard, 1975. Author: Joseph A. Carr

Telephone switchboard, 1975. Author: Joseph A. Carr

A peer needs to communicate its network terrain, e.g. its public IP address, whether it’s behind a NAT, and its private IP address. It usually can’t get this information itself, so it connects to a remote STUN server via the WebRTCPeer.create_offer() command, which gives it this network description. When the description (an offer) is created, the WebRTCPeer signal offer_created is called. The client must set the offer as its local description and send the offer over the signaling server to the other peer, who sets it as the peer’s own remote description. The full signaling process for two peers, Alice and Bob, is as follows:

- Alice creates an offer using

create_offer(). - On the

offer_created signal, Alice calls set_local_description() with the offer and sends it over the signaling server to Bob. - Bob calls

set_remote_description() with the offer, which automatically creates an answer to the offer. - When the answer is created,

offer_created is called again (an answer is really the same thing as an offer: just a network description). - On Bob’s

offer_created signal, Bob calls set_local_description() with the answer and sends it over the signaling server to Alice. - Alice calls

set_remote_description() with the answer.

Bob and Alice also need to share how exactly they will be communicating. The routes they may take to communicate are known as Ice Candidates and must be shared as well. When a new Ice Candidate is created, WebRTCPeer will call the new_ice_candidate signal. The client must then take the new Ice Candidate and send it over the signaling server as well. Any candidates a client receives from the signaling server should be added to the WebRTCPeer with add_ice_candidate().

Once all offers and ice candidates are shared, the two clients will now be connected as peers and will be able to freely communicate directly. Using the PacketPeer subclass, WebRTCPeer, or the NetworkedMultiplayerPeer subclass, NetworkedMultiplayerWebRTC.

Current progress

As of now, WebRTC is only a module (compiled within the engine, not plug’n’play as GDNative would allow), and it only runs on native platforms. We have tested it successfully on Linux and Windows. A WebRTCPeer class inherits from PacketPeer, so that two peers are able to send back and forth Variants via put_var() and get_var() as well as raw data via put_packet() and get_packet(). To connect to more than one peer, additional instances of WebRTCPeer must be created. NetworkedMultiplayerWebRTC does not yet exist.

WebRTC requires specifying ICE servers (STUN and TURN servers) but currently GDScript cannot directly set the servers.

All necessary signals are available in GDScript in the WebRTCPeer class. An additional signal, notify, exists to send debug messages from WebRTC. For the sake of thread safety, WebRTCPeer adds all new signals to a queue. For them to be called, WebRTCPeer must regularly be polled with WebRTCPeer.poll().

Future steps

Much of this information about how to use WebRTC in Godot may become obsolete within the next month. The API is still subject to change. We are currently working on creating the NetworkedMultiplayerWebRTC class, meaning the existing networked multiplayer Bomberman and Pong demos will soon work with WebRTC with minimal modifications. After that, our priority is to complete HTML5 support. Finally, if we have time, we will move the third party WebRTC code to a GDNative extension to preserve the small size of the Godot binary and source files.

WebRTC should be fully usable and available to the public in Godot by the end of Google Summer of Code, but the GDScript API will likely continue to change to aid ease of use and flexibility. Additionally, outside of the scope of Summer of Code, I plan to make sample scripts that demonstrate how to use a signaling server over TCP with PacketStream and over WebSockets.

Final thoughts

I’d like to take this moment to thank my mentors, Fabio Alessandrelli (fales) and Max Hilbrunner (mhilbrunner) for all they’ve done this summer. I would be at a loss trying to complete this project on my own, without their help and guidance. Thank you as well to Godot’s project manager, Akien, for all his help and to the welcoming Godot community.

To any future GSoC students that might read this, if you have never contributed to an open source project then I can say first hand that Godot, between its friendly contributors and its surprisingly detailed docs, is a fine place to start.

Gear VR and Daydream support – Paritosh Sharma

- Project: Support for Gear VR and Daydream devices via a GDNative module

- Student: Paritosh Sharma

- Mentor: Bastiaan Olij (Mux213)

- Repository: https://github.com/GodotVR/godot_gearvr and https://github.com/Paritosh97/godot/tree/google_vr

Introduction

Thanks to Google and Godot for giving me an opportunity to work on this. My GSoC project mainly involves creating a GDNative module for Oculus mobile devices and binding an Android module in Godot’s core which enables support for the Google VR SDK.

Roadmap

I wasn’t much experienced with either Godot or Android initially, but this is what I’ve done so far and plan to do further:

Done June - July 2018

- Understanding the existing GDNative APIs and modules

- Understanding Oculus’ VrApi

- Adding GDNative Android API to core

- Implementing Gear VR GDNative module

- Compiling Gear VR GDNative module

- Initialize VrApi on the Device

- Understanding the Google VR Android SDK

- Writing boilerplate for Google VR

Planned for August 2018

- Stereo rendering for Oculus mobile devices

- Implementing VrApi Input API

- Stereo rendering and Tracking for Google VR

Planned after GSoC

- Compiling Android modules using Scons

- Spatial Audio and User Input for Google VR

- Spatial Audio for Gear VR

- Start on Oculus Avatar and Platform SDKs

- Start on Cardboard for iOS

Details about work done till July 2018

Understanding the GDNative interface

I started off by giving time to study the existing GDNative ARVR API and its modules, especially the Oculus Rift one.

Understanding Oculus’ VrApi

Most of my experience with both Rift and Gear VR was on Unity. Thus, I had to understand the Native Mobile SDK for Oculus’ mobile devices. Luckily, Oculus already had a Native Engine Integration guide in their docs.

Thus, after forward and reverse engineering a few samples, I was able to get some of my concepts clear.

Adding GDNative Android API to core

We needed to provide some references from Godot’s Android platform in order to use the JNI, which will subsequently be used to initialize VrApi.

I went through this great post which shows how to compile and use JNI from GDNative.

The only thing left was to officially add the GDNative Android API in Godot core. This was done with some help from my mentor Mux213 and we were good to go.

Implementing GDNative module for Gear VR

Mux213 already completed the Rift’s GDNative module and already made a start on the Gear VR.

We had the JNI references from Godot.

On top of that we had the Cocos’ Gear VR SDK to refer from.

Thus, things weren’t complicated from here on. Be it initializing, applying head tracking, getting eye transform and filling eye projection.

Compiling Gear VR GDNative module

For now, the Gear VR GDNative module or any other Android GDNative module has to be compiled using the legacy ndk-build script.

Although, I have been working on switching to Scons mostly by studying how Godot uses it.

Initialize VrApi on the device

Alright, enough with the boring text, let’s skip to install the demo project on my Galaxy S7.

Right off the bat you will see the following screen:

Inserting the device into the Gear VR headset (or switching to Oculus Developer mode), we see the following screen:

So Oculus mobile apps are supposed to be signed with an Oculus signature file which can be generated from here.

Next, we need to put that file in assets folder in the APK and sign it.

Next we tell Godot to copy this non-resource file while building the APK.

Unfortunately, my version of S7 comes with the Adreno 530 GPU which isn’t GLES3 friendly (this will improved in Godot 3.1 with the GLES2 backend). Thus, the app crashes after this step. But we get this with logcat.

To compare with, here’s what logcat looks in case of missing signature.

We see the ovrDistortionMeshHeader and the TrackingServiceClient get initialized in the former and a failOsig message in the latter.

Understanding the Google VR Android SDK

The Google VR SDK includes support for both Cardboard and Daydream devices. I spent some time studying the existing samples and other Android Modules.

Writing boilerplate for Google VR

To include the Google VR SDK, we simply had to add the various com.google.vr dependencies in config.py.

Much of the API loading code was inspired from other modules.

Unfortunately, I lost few of my local commits and don’t have any cool screenshots but we should get the stereo rendering and the tracking working soon.

GSoC experience

Working at Godot has been great. The guys at IRC have been very helpful even before GSoC began. Bastiaan has been a great mentor and helped me with each and every hurdle.

I want to explore a lot more in Mobile VR and both GSoC and Godot have helped me a lot in doing so.

Future

A lot of stuff is yet to be implemented. Keep checking GodotVR frequent updates.

The code

You can see all of the commits for Gear VR here. Code for the Google VR module will be uploaded soon.

Thanks

On behalf of the Godot community, a big thankyou to all students involved in our GSoC program this year, as well as all the mentors who give some of their time to help students reach their project’s goals. And finally thanks to Google for organizing GSoC each year and sponsoring the development of free and open source software, as well as giving students the opportunity to get professional experience.