This is Pedro J. Estébanez, a.k.a. RandomShaper in the Godot community.

You may already know that I have been implementing a Direct3D 12 rendering driver for Godot. Since the announcement that W4 Games donated my time working on that to the project, the code has received a lot of maintenance. In fact, the pull request still hasn’t been merged since there has been a continuous flow of improvements.

In this article I’d like to discuss specifically how I faced some of the challenges posed by different aspects of making shaders work. This was by far the most technically interesting area. Be warned that this piece is dense in technical information.

Translation of GLSL/SPIR-V to DXIL

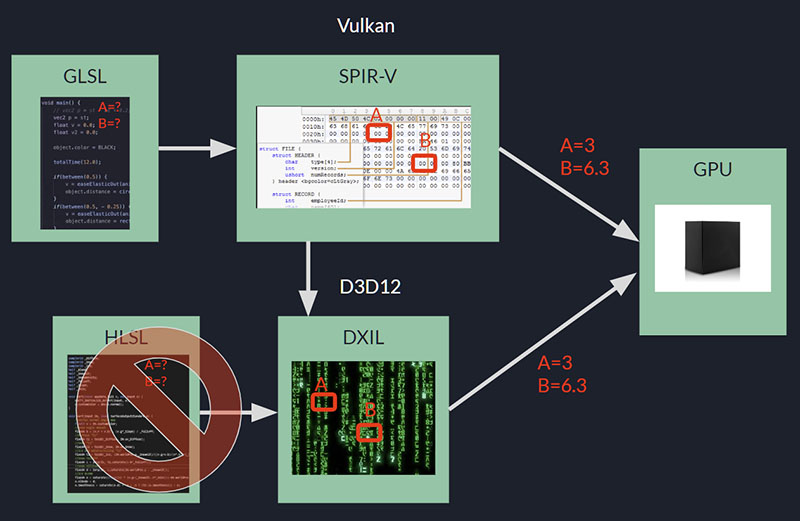

Godot’s rendering architecture is built with the industry standard Vulkan graphics API in mind. And that’s great! However, once you want to plug new rendering APIs into the engine, you’ll find that some elements need to be wired in a manner that they work with the alternative API (Direct3D 12 in this case).

Shaders in Godot are written in its custom, very GLSL-like language. (The builtin shaders are already GLSL in the source code.) Shader code in this language is compiled by the engine (thanks to glslang) into SPIR-V, which is a well-defined format that stores the binary representation of a shader.

SPIR-V and Vulkan play nice. However, Direct3D 12 features its own binary shader format: DXIL. This format is structured as a container with its most important contained chunks being shader metadata and the compiled shader code in the form of LLVM bitcode (yes, the same kind of bitcode LLVM/Clang uses for an intermediate representation of the compiled code). As a consequence, this rendering driver would need a way to generate DXIL from either the GLSL or the SPIR-V representations of the Godot shaders.

First round: SPIRV-Cross

After assessing the available third-party libraries and open source projects capable of doing that (and license-compatible), I found SPIRV-Cross was the most sensible choice: it would translate GLSL to HLSL (the high-level counterpart of GLSL in the DirectX world). From that point, the D3D12 renderer would use the standard DirectX Shader Compiler library to compile HLSL into DXIL.

That worked quite well, but wasn’t without big headaches about writing the code that should match the resource bindings in the Vulkan-targeted shaders to those in the DXIL ones. I won’t delve into details on that here. Just know it required an insane amount of code and relying on certain SPIRV-Cross specifics. For now, the takeaway is that it was a hell of an approach, but worked in practice! (If you’re curious, in the first version of the pull request, you can see for yourself what I’m talking about.) This process also allowed me to make a few little contributions to SPIRV-Cross itself and learn its internals, which is always a good thing.

Second round: Via Mesa’s NIR

Months went by and I verified that Microsoft was making great progress with Dozen, the Vulkan-to-D3D12 translation layer found in Mesa.

Mesa was already capable of translating SPIR-V into its own intermediate representation (NIR), but Dozen would have added the ability to translate NIR to DXIL. That looked very promising because it would be a binary-to-binary translation (i.e., SPIR-V to DXIL). This would avoid having to go all the way back to a high-level language (GLSL/HLSL), which is slower and less convenient.

With some experimentation, I could make a shell script (included in the source code of the D3D12 renderer) that extracts from the Mesa source tree the relevant pieces of code to make the SPIR-V to DXIL translation possible.

I wouldn’t say that this integration was a piece of cake, but had major benefits in comparison to the SPIRV-Cross-based approach. For instance, the bindings matching issue was easily solved by a Godot-specific patch to the Mesa code by which the translation process gets some callbacks. With that mechanism, the D3D12 renderer is told about the original set-binding pair of every resource in the SPIR-V shader and then it trivially maps them to some register indices in the DXIL world with some simple arithmetic:

DXIL register = SPIR-V set * 100000000 + binding * 100000

A couple of notes on this:

- We can make such a liberal use of DXIL registers since they are logical, just a way of tagging the bindings. (In past versions that was not the case, as far as I can tell.)

- Regarding the last multiplication, if we understand Vulkan numbered bindings as “slots” and so we do with Direct3D register indices, in principle there would be no reason for it. However, Vulkan slots can hold entire arrays, whereas D3D ones need one slot per array element. Therefore, with that multiplication we are reserving a big range of D3D bindings to account for however big a incoming Vulkan array may be.

The operation of mapping the Vulkan resource types (image, buffer, etc.) to their D3D12 counterparts (SRV, UAV, etc.) is not trivial. The exact resource type depends on extra attributes that decorate each binding, and even on actual usage! With the SPIRV-Cross approach, the Godot D3D12 renderer needed to do reflection on the DXIL shader to find out the D3D12 types the Vulkan ones ended up being mapped to (reflection was used for the bindings, too). In contrast, with the NIR-based approach, the callbacks mentioned earlier can also get information about which kind of Direct3D resource each binding is being translated to, on the go.

In conclusion, the NIR-based approach was kind of uncharted territory, but turned out to be much more convenient. I had to make a few PRs to Mesa to add or fix little pieces of translation logic to this part of Dozen, though. But again, that’s a great learning experience.

Specialization constants (creatively working around the lack thereof in Direct3D)

For the first version of the PR (the SPIRV-Cross + DirectX Shader Compiler way) I published a Twitter thread explaining how I approached this problem. Some parts are still true in the NIR-based PR. In any case, in this writeup I’m doing the full updated explanation of how it works now, so there’s no need to read the other one.

Vulkan features specialization constants (SCs from now on), which are some sort of compile-time constants in terms of optimization of the final shader code that runs on the GPU (branch pruning, informed loop unrolling, etc.). However, these are much more flexible, as they can be applied at runtime to create the graphics/compute pipelines with shaders already compiled to SPIR-V.

The closest in Direct3D is actual constants or preprocessor definitions in the HLSL code. That means that, in order to create multiple pipelines corresponding to different variants of the same shader, you have to compile multiple versions of the HLSL code with different values set each time at the source code level.

SPIRV-Cross does some work of assisting with that, making the process of patching the source code a bit more ergonomic, but the issue of having to re-compile the source is still present. Moreover, the PR in its current, definitive form is using an approach where the source code is not used at all (neither in GLSL nor translated to HLSL). Therefore, some way of applying different values to SCs for shaders compiled to DXIL is a must. (In the SPIRV-Cross way it was a nice-to-have feature, but patching HLSL and recompiling, even if very slow and forcing to store the source code in the shader cache, would have done the trick.)

The way Mesa approaches SPIR-V SCs is applying their values very early in the translation to NIR. In other words, a NIR representation is hardcoded to some specific set of SC values. That in turn leads to multiple DXIL versions of the shader. We don’t want that. Instead, our goal is to have a patchable DXIL blob (per shading stage) where the SC values are still unknown.

1. Dynamization of SC operations in SPIR-V

The SPIR-V specification defines a number of opcodes related to SCs, like declaring a SC that is true or false by default (SpvOpSpecConstantTrue/False) and doing logic/arithmetic on one of them (SpvOpSpecConstantOp with sub-opcodes for the specific operation).

Upstream Mesa’s SPIR-V to NIR code follows the SPIR-V specification on how to apply the SCs. In short, it replaces all the default values of them with any that has been provided by the caller code to specialize the shader and then runs all the operations offline with those now known values, “fossilizing” the shader on them. That unleashes optimizations like pruning conditional branches or pre-computing arithmetic operations wherever there are SCs involved, now their values are solid constants.

What I needed is that those operations are not performed offline, but be promoted to true dynamic operations, as if the original GLSL had used non-constant variables instead of SCs, and therefore not optimizable by now.

Mesa’s SPIR-V to NIR code is patched in the Godot D3D12 renderer to do precisely that. The values of the SCs are set to some carefully chosen magic sentinel value plus the SC id, so in a later step we can tell if a literal value corresponds to an SC, and which one.

Some extra NIR operations are added depending on the type of the SC. For instance, for a float, there’s some bit casting so the base value can be treated as a plain 32-bit integer but the shader eventually sees it as a floating-point value and thus does the right thing with it once patched.

2. Prevention of NIR level optimization

Mesa’s NIR machinery is powerful. It can apply a variety of optimization passes to the NIR representation of a shader. That’s awesome, but an issue for us because if we don’t inhibit it somehow, we end up again with a “fossilized” shader, only that this time it’s obeying some weird sentinel values instead of sensible SC values. Whatever the case, that’s bad for our purposes.

The core issues lies in the fact that NIR has a load constant opcode (nir_intrinsic_load_constant), which is used to “load” the sentinel value into some virtual register, and that the myriad of optimization passes NIR is run through can optimize it out (if it’s possible to pre-compute some ALU operation or however else take a static decision about the fate of that value, for instance).

The solution was simply to invent a new opcode (nir_intrinsic_load_constant_non_opt), which works exactly like the original one, but, by being in the end another one, is unkown to the optimization passes, which have no option but leaving it in place.

3. Obtaining patchable DXIL

The last thing we ask Mesa to do for us is generating DXIL from the nicely patched NIR we have at the moment. But our “deliverable” consists also of a table of the bit offsets to patch in the DXIL for each SC id.

I patched the code that emits constants to the DXIL stream so that it recognizes cases of SCs if they match the sentinel value mask. The rest of the bits are the SC id. On each occurrence, the corresponding callback is leveraged to provide the information to the Godot D3D12 driver. (It’s a bit more complicated than that, since the offset in the bitcode has later to be adjusted to match where the DXBC chunk ends up in the whole DXIL blob.)

4. Creating pipelines with patched DXIL

The Direct3D rendering driver is now able to apply whatever specialization constant values are needed to the already compiled shader, which was our initial goal.

Now I have to mention that LLVM bitcode is an akward beast and that it’s not trivial to patch a miserable integer due to variable bit-rate encoding. (Speaking of that, the former approach I implemented had a limit on the number of bits that could be patched. This imposed big limitations in the usable range of integers and imposed an elephant-sized epsilon for floating point ones; those have been happily lifted in the current one.)

This is the comparison of the assembly code produced by the same shader, only with different SC values, which allowed in the second case to optimize out a multiplication:

Microsoft may very well end up adding SCs natively to Direct3D. Nonetheless, in the current state of things this hack/technique/magic is very close to what real SCs would be in terms of performance. The ISA assembly takes the patched values into account so it can run its own informed optimization passes. This way, it can provide a late form of what we were making an effort to prevent at earlier stages. Maybe the biggest downside is that the DXIL blob has to be validated-signed every time it’s patched. This takes some extra time and forces us to include the dxil.dll file with the binary distribution of the engine.

Closing words

First of all, if you have reached here, you’re amazing and thank you for reading. I really wanted to share the story of my adventures in this territory.

My ways into this issues may or may not be the best, but what I’m pretty sure about is that they are at least interesting or exotic enough for people interested or curious about these topics.

Support

Godot is a non-profit, open source game engine developed by hundreds of contributors in their free time, and a handful of part or full-time developers hired thanks to donations from the Godot community. A big thank you to everyone who has contributed their time or financial support to the project!

If you’d like to support the project financially and help us secure our future hires, you can do so on Patreon or PayPal.